In this episode of the podcast we explore Chapter II- Variation Under Nature from the 6th edition of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species. One of the big themes Darwin explores in this chapter is the arbitrariness in defining a species and how to differentiate species from a variety or subspecies.

Sarah brought up the example of ring species, in particular we talked about the herring gull species complex that circumnavigates the northern hemisphere. The ring species model (also called rassenkreis) of speciation was first developed in 1942 by Ernst Mayr (yes, the same Ernst Mayer mentioned by Josh) and it proposes that as a population disperses around a large scale geographical barrier (e.g., ocean, mountain ranges, etc) the sub-populations diverge genetically with distance from the ancestral original population. Ultimately when these sub-populations meet again on the other side of the barrier they have diverged so much as to become reproductively isolated. In our conversation we discussed the herring gull species complex and mentioned the salamander species complex from the California central valley as examples of ring species. More recent research has questioned if these two are actually examples of Mayr’s ring species model but instead are products of the standard allopatric speciation model which requires the populations to become reproductively isolated from the parental population and speciation occurs as the sub-population become adapted to their local environmental conditions.

Regardless of the speciation model that is occurring, the herring gull complex exhibits a great array of interbreeding subpopulations that blurs the line between species and subspecies and it illustrates intermediate forms in the speciation process. The figure below is from a 2004 paper that challenges the view that the herring gulls are an example of a true rassenkreis.

Figure on the left represents the classic view, as described in our

podcast, of how the herring gull species complex came about. The new

alternative mode, figure on the right, reveals multiple origins, allopatric speciation

events, and more complex dispersal patterns.

We also discussed Carl Linne’ (Linnaeus) and the organization

scheme he proposed in 1735 that involves nested hierarchies: Kingdom > Phyla

> Class > Order > Family > Genus > Species which we still use

today. James noted how Linnaeus looked

like Ed Asner with a wig and questioned Linnaeus’ decision to use himself as

the type specimen for all Homo sapiens.

|

| Modern Carl Linnaeus as portrayed by Ed Asner |

|

| Type specimen that represents all humans |

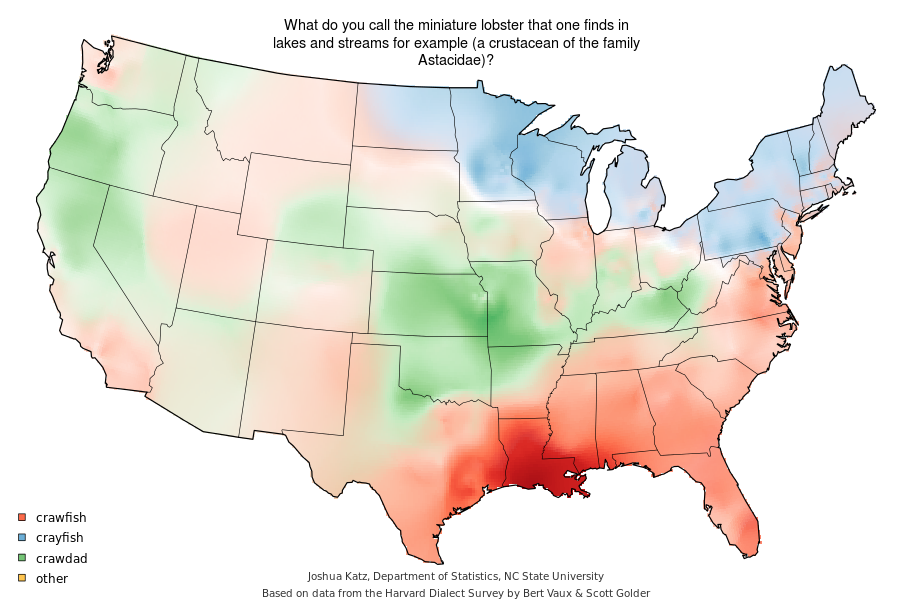

We also discussed regional dialects and mentioned a great

website (http://spark.rstudio.com/jkatz/SurveyMaps/)

where you can compare how various words

and phrases are used around the United States. Here is the map James referred

to in the podcast concerning the use of the term crawdad or crayfish or

crawfish.

Go here if you want to map the geographical origin of your

own linguistic tendencies.

Interlude music within the podcast is "Maccary Bay" Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com) Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Interlude music within the podcast is "Maccary Bay" Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com) Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

hi!

ReplyDeleteI've been listening to your podcast for a bit, great work! thank you!

So, I was puzzled by your long (and still entertaining ;) discussion of Darwin's statement "species are arbitrary". I didn't get what was so troublesome about that claim. Because, "species" is after all a human-made category projected onto the continuous and dynamic fabric of reality. Just like, I mean, all the words.

My guess why it made a sensation "back then" is that when Darwin said it, he had to contend with some staunchly essentialist views, such as religious fixism, but it hardly sounds very radical to my millenial ears.

Then again, I'm not a biologist so I'm certainly missing a lot of context!

Any thoughts?

Thank you so much for listening to our podcast and your kind words.

DeleteIn terms of your question, I would argue that even to modern ears, saying that what is A species is arbitrary can be controversial, especially if your model is of special creation. But it is even challenging if you are a secular naturalist.

For example, if we accept the notion that species are arbitrarily determined, does it invalidate the Endangered Species Act? If all species are arbitrarily determined then what is it we are trying to protect?

Of course, I am not advocating the elimination of endangered and threatened species list but we are applying static terms to dynamic systems. It does have its problems.

Thanks again for listening and taking the time to comment. We appreciate it!

"A species is arbitrary can be controversial, especially if your model is of special creation."

ReplyDeleteRight but as I understand it that "model" has long been booted out of established scientific debate, hasn't it? That's kind of like taking a flat earther's perspective into consideration when discussing astrophysics. But maybe I dismiss such views so easily because I live in Europe where creationism is essentially a thing of the past.

I did find your point about the need to accurately define species in the context of environmental law absolutely illuminating.

Still, that felt kind of adjacent to the actual exegesis of Darwin's position, and frankly to actual theoretical biology.

I mean, I have a hard time imagining scientists going: "uh-oh, based on the data, it would appear species are not a thing that exists. But, it would be irresponsible to say so, because there's all these regulations that rely upon this messy concept. So, let's all pretend species really are well-defined, discrete categories." (under their breath: "damn you, Darwin and your big mouth!!!")

You know what I mean?

Sure scientific concepts need to be translated into legally-actionable handles. And sure, that's really important and complicated work, power to the science folk and law folk engaging with each other to come up with the best possible way of leveraging science to formulate and enforce policies.

But. does that mean we can't afford to embrace darwinism completely? Would you say that it be irresponsible to do away with essentialism in theoretical biology, because then the science would no longer be politically usable?

Or am I just confused?? I mean, I probably am, being as a little knowledge is a dangerous thing :D